Beachwood Canyon in the 1940 Census, Part IV: Familiar Names and Addresses

June 7, 2012 § 2 Comments

The 1940 Census is numbered sequentially only to a point; it jumps from street to street on any given page, making the search for specific names and addresses time-consuming and difficult. Fortunately, I’ve been able to locate some of the notable Beachwooders who appear in my documentary “Under the Hollywood Sign.”

First among them is Charles Entwistle. After the actress Peg Entwistle’s suicide off the Sign in 1932, her adoptive parents–her paternal Uncle Charles and his wife Jane–remained in their house, which still stands, at 2428 N. Beachwood Drive. In 1940, Charles was 75; Jane was 55. Both were retired from their acting careers, listing no occupation or income on the Census. The other resident of the house was their younger nephew Robert Entwistle. At 21, he was working as a bookkeeper in a bank and earning $898 annually, $14,758 in today’s terms. His older brother Milt was not listed; at 23 he had left the household, possibly for the Navy, in which he served during WWII.

The Entwistle Family, line 12/All photos courtesy http://www.the1940census.com

A half-mile southwest of the Entwistles lived the Theosophists Henry Hotchenor, aged 58, and his wife Marie, aged 69, at 6139 Temple Hill Drive. Marie Russak Hotchenor, the architect of Moorcrest, also designed their Moorish-Spanish stucco house, which stands directly across the street from Moorcrest. Interestingly, Henry listed his occupation as “manager of own real estate,” while Marie claimed no occupation.

Finally Albert Kothe, caretaker of the Hollywood Sign and Wolf’s Lair, appears at the address where he lived from the mid-1920s until about 1960, when his dwelling was torn down: 3200 N. Beachwood Drive. His home, a foreman’s cabin dating from the days when Hollywoodland’s stone masons lived in tents on the property (1923-1925)–was located at the northern edge of Beachwood Drive, where the dirt road to Sunset Ranch begins. The certainty of his address should lay to rest the enduring myth that Kothe “lived in a shack behind the Hollywood Sign.” In the Census, Kothe listed his occupation as laborer for a private employer; he earned $800 a year ($13,148 today).

Background information about the Entwistles, Hotechenors and Mr. Kothe can be found in previous posts.

The Hollywood Sign and the Eiffel Tower: Monuments to Modernity, With Differences

October 25, 2011 § 3 Comments

The monument that is mentioned most frequently in conversations about the Hollywood Sign is the Eiffel Tower, and for good reason. Both became icons by accident, having been conceived as temporary structures, and grew to represent the cities in which they are located. Both were built during the Machine Age and project the dynamism of that era. Finally, both monuments are abstract symbols, allowing their admirers to imbue them with a variety of meanings. Just as the Hollywood Sign can symbolize the movie industry, fame, or its physical location, the Eiffel Tower can embody the Belle Epoque, the City of Paris or a triumph of engineering.

There are, however, important differences. While Gustave Eiffel’s iron masterpiece wasn’t supposed to be permanent, it certainly looks as if it were built for the ages. An engineering marvel, it was the tallest man-made structure in the world upon its completion in 1889. Its base, particularly the curved spans that support its legs, somehow manages to be both massive and delicate. To stand under it, as I did during a recent visit, is to see a breathtaking array of lacy patterns whose beauty belies their strength. As charming as the Tower is from a distance, it provides an even greater visual thrill a close range.

By contrast, in its original incarnation (1923-1978) the Hollywood Sign wasn’t engineered at all. The letters were anchored from behind by telephone poles, rather than bolted to a foundation. Unsurprisingly, over the years assorted letters were knocked down by windstorms and, in the case of the H, by an out-of-control car driven by the Sign’s caretaker, Albert Kothe. After the old Sign was torn down in 1978, its replacement–the present-day version–was skillfully engineered. Caissons were sunk into the bedrock, and the new corrugated steel letters were bolted to a heavy steel scaffolding. In its 33-year history, the current Sign has never moved, whether during earthquakes or windstorms, or required any repairs.

Perhaps because both my grandfathers were engineers, I have a great fondness for the back of the Hollywood Sign, where its support structure can be seen. The helicopter pilot on my aerial shoot told me that, to his knowledge, I was the only person who ever shot the back of the Sign. I also shot the back from the ground at close range, both on video and in still photos.

The front of the Sign is another story. At close range, its corrugated steel resembles nothing more than an industrial fence, and projects the same appeal. The Hollywood Sign can only be appreciated at a distance, where its 45-foot letters can be read.

Which brings me to another difference. The fact that the Hollywood Sign is composed of letters that make up a word sets it apart symbolically from the Eiffel Tower. Though both monuments represent modernity, the Sign’s “wordness” (to quote Leo Braudy) gives it an abstraction that goes beyond any meaning attributed to the Eiffel Tower. By virtue of its height, the Eiffel Tower projects a common message that the Hollywood Sign does not. Which, of course, explains the Sign’s appeal to tourists in search of a photo opportunity. Standing in front of the Eiffel Tower, you’re an ant–albeit one that has traveled to Paris. But in front of the blank white letters of the Hollywood Sign, it’s all about you, the potential Hollywood star.

Hollywood Sign Truth and Fiction, Part II: Leo Braudy’s Book

September 19, 2011 § 6 Comments

Leo Braudy is a USC professor and pop culture critic whose latest book, The Hollywood Sign (Yale University Press, 2011) is an everything-but-the-kitchen-sink look at Hollywood–the Sign, the place and the industry–as well as the culture at large. In attempting to cram huge swaths of Los Angeles’ history into 192 pages, Braudy turns his hummingbird-like attention to topics ranging from A (the Academy Awards) to Z (the Zoot Suit Riots), touching upon each so briefly that the result is less a book than a dizzying exercise in name-dropping. (The index lists 24 entries under “A” alone, including Fatty Arbuckle, Ansel Adams, Gene Autry and Angelyne.) For the reader, The Hollywood Sign is less exhaustive than exhausting: if you’ve ever wanted a book to unite Marcel Duchamp, “101 Dalmations” and Laura Ingalls Wilder, this one’s for you.

In the midst of this pop-culture stew, Braudy does one thing brilliantly: deconstructing the Hollywood Sign. For all the ink that has been spilled over the Sign’s meaning and appeal, no one has improved upon his analysis:

Its essence is almost entirely abstract, at once the quintessence and the mockery of the science of signs itself….It isn’t an image that looks like or refers to something called Hollywood; it is the name itself. Yet people everywhere recognize it as the symbol of whatever “Hollywood” might be–with whatever ambiguity is part of that meaning.

Braudy also emphasizes the Sign’s unique interactive quality, in which its admirers become the admired:

Seeing the sign lets you know you are in Hollywood, that special place. Photographing it enhances your own sense of identity….Instead of looking at the Liberty Bell or the Lincoln Memorial and appreciating their importance and the history they represent, we look at the Hollywood Sign and it looks back at us, enlarging our sense of our prestige by its symbolic aura.

Nevertheless, Braudy makes more than his fair share of factual errors. Despite residing in Los Angeles, he seems not to have spent much time in the Hollywood Sign’s vicinity, confusing Mulholland Highway with Mulholland Drive and asserting that Hollywoodland’s staircases “were less functional than picturesque” as “few of the new inhabitants would be traipsing up and down” because they owned automobiles. (In fact, Hollywoodland residents have always used the stairs to get from their homes to Beachwood Village, which has a market and bus stop. In the early days of one-car households, people had to walk; now they do so for convenience and exercise.)

More serious are the mistakes he makes about Albert Kothe, the Sign’s caretaker, and Peg Entwistle, the Sign’s only suicide. In repeating the fiction that Kothe “lived in a shack behind the first ‘L’,” Braudy concocts a full-fledged conspiracy theory about Peg’s death.

And where, while [her jump from the Sign] was going on, was Albert Kothe…..Could Peg Entwistle have been killed elsewhere and the scene at the sign staged?

This astonishing question comes on the heels of Braudy’s assertion that Peg couldn’t have climbed to the Sign due to its distance from her house (which he puts at “three or four miles,” though the route she took was closer to two) and steepness, her lack of athletic clothing and, most bizarrely, her “trudging her way on foot in an area designed only for cars.”* Yet Braudy apparently thinks it’s possible that someone (who?) killed Peg (why?) and transported her body (how?) up to the Hollywoodland Sign, steep grade and lack of running shoes notwithstanding.

The murder theory is ludicrous; beyond that, it is hurtful to Peg Entwistle’s surviving family. But it probably will be treated as fact, thanks to Braudy’s reputation and the power of the Internet. It’s discouraging that despite my efforts and those of James Zeruk, Jr. (whose biography on Peg is nearing publication), the lies about Peg Entwistle keep coming.

Disclosure: I briefly met Leo Braudy at a reading soon after the publication of his book. When I asked if he had heard of me or my documentary, “Under the Hollywood Sign,” he said no. In light of the above, I believe him.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

*Beyond the fact that Peg Entwistle was an athletic 24-year-old, it should be remembered that most Americans in 1932 routinely walked long distances in regular shoes.

Related articles:

https://underthehollywoodsign.wordpress.com/2009/05/19/peg-entwistles-powers-of-persuasion/

Albert Kothe: A German Immigrant’s Life in Hollywoodland, Part II

April 18, 2011 § 2 Comments

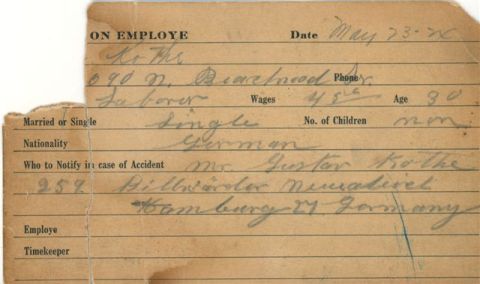

Albert Kothe no doubt left Hamburg for economic reasons, as jobs were in short supply in Germany’s ruined post-WWI economy. He seems to have earned his passage to America as a merchant marine, judging from a shipboard photo. How Kothe wound up in Los Angeles is unclear, but he quickly made it his home: among the artifacts found after his death was this certificate for a citizenship course, dated 1933.

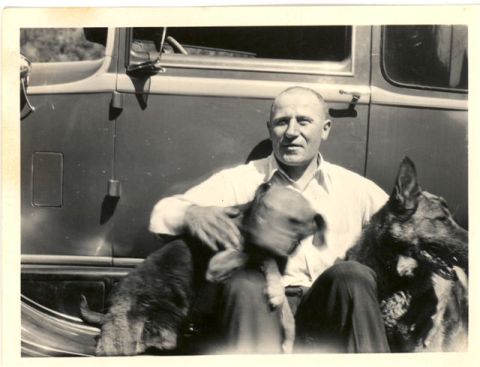

His photos tell the story of a bachelor existence enlivened by female friends, letters and postcards from home, his dogs and–most of all–cars. Kothe seems especially proud of this car, judging from the number of photos in which he appears beside it.

Because he didn’t own a home, first renting the cabin at 3200 N. Beachwood Drive and later an apartment behind the Beachwood Market, Kothe’s car ownership symbolized the American Dream. In the 1940’s, Kothe earned local notoriety when, during an inebriated visit to his old workplace, his car spun out of control and knocked down the letter “H” of the Hollywoodland Sign. (The righted and repaired letter– already infamous as Peg Entwistle’s jumping-off point–somehow survived until 1978, when the old Sign was torn down and the current version built.)

Because he didn’t own a home, first renting the cabin at 3200 N. Beachwood Drive and later an apartment behind the Beachwood Market, Kothe’s car ownership symbolized the American Dream. In the 1940’s, Kothe earned local notoriety when, during an inebriated visit to his old workplace, his car spun out of control and knocked down the letter “H” of the Hollywoodland Sign. (The righted and repaired letter– already infamous as Peg Entwistle’s jumping-off point–somehow survived until 1978, when the old Sign was torn down and the current version built.)

Ironically, in light of his penchant for drinking and driving, Kothe went on to drive the Hollywoodland jitney, a job he apparently relished. The last incarnation of Hollywoodland’s neighborhood bus, Kothe’s woody wagon carried residents from the bus stop in Beachwood Village to their hillside homes. Service ended sometime in the 1950s, probably because most families had two cars by then.

In the early 1960s Kothe moved from his cabin to Beachwood Village, where he lived in an apartment owned by the Williams family. A neighborhood fixture, he enjoyed a certain fame, both local and national, for having changed the lightbulbs on the Hollywood Sign. He died in 1974, at the age of 81, having lived in the Sign’s shadow for more than half a century.

In the early 1960s Kothe moved from his cabin to Beachwood Village, where he lived in an apartment owned by the Williams family. A neighborhood fixture, he enjoyed a certain fame, both local and national, for having changed the lightbulbs on the Hollywood Sign. He died in 1974, at the age of 81, having lived in the Sign’s shadow for more than half a century.

Albert Kothe: A German Immigrant’s Life in Hollywoodland, Part I

April 13, 2011 § 2 Comments

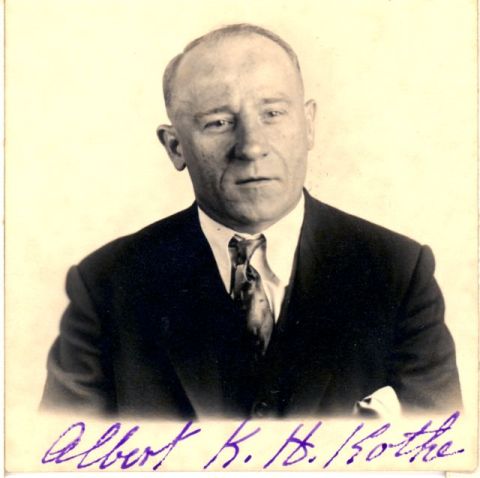

Straight Outta Hamburg/All Photos Albert Kothe Family Archive, courtesy Harry Williams, unless otherwise noted

Albert Hendrick Kothe was born in Hamburg, Germany in 1893. After World War I, he made his way to America and settled in Los Angeles, where he found work and a new home in Hollywoodland. Like so many Canyon residents, Kothe lived out his life here, in the process becoming a neighborhood fixture, a Zelig-like figure–and something of a local legend.

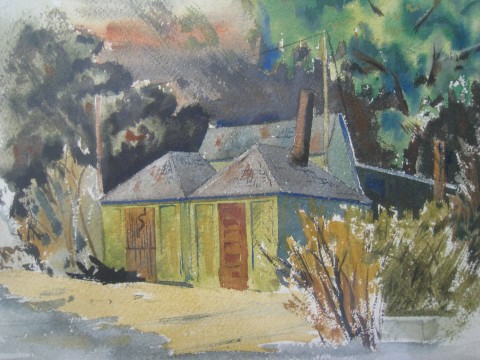

Albert Kothe may or may not have helped to build the Hollywoodland Sign, but he certainly was its caretaker upon its completion in July, 1923. His job, which probably lasted until 1939, was to change the 4,000 lightbulbs that lit the Sign at night, a Sisyphusian task for which ladders were kept permanently propped against the Sign’s back. Though Kothe undoubtably spent a great many daylight hours on Mt. Lee, he didn’t actually live there. (The myth that Kothe “lived in a shack behind the first L” is so pervasive that Leo Braudy repeats it in his new book The Hollywood Sign [Yale University Press, 2011] Oops.) Although there was a shed behind the Sign, it housed lightbulbs and other equipment, while Kothe resided in a cabin at the north end of Beachwood Drive. (The cabin was probably built for the foreman of the stonemasons who built the Hollywoodland walls and stairs from 1923-25. The stonemasons lived in adjacent tents.) The cabin, which was torn down for houses 50 years ago, looked like this:

When the Hollywoodland Realty Company stopped maintaining the Sign in 1939, Kothe found work at Wolf’s Lair, a house large enough to require a full-time handyman. Kothe’s employment by Bud Wolf has satisfying parallels in literature and movies, for the two men at first glance were polar opposites: Wolf a rich, companionable bon vivant; Kothe a poor laborer and lifelong bachelor. But in truth, they were flip sides of the same coin–uncompromising, somewhat eccentric men who discovered their niche in Hollywoodland, and stayed.

Next time: Kothe’s latter years–and automotive adventures.

Why the Hollywood Sign Isn’t Lit (and Never Will Be)

November 3, 2010 § 64 Comments

The Hollywoodland Sign at Night, circa 1925/Courtesy Los Angeles Public Library, Security Pacific Collection

One of the perennial questions about the Hollywood Sign is why it isn’t lit at night. The answer is that the Sign overlooks a residential neighborhood whose access narrows from a two-lane road to a steep, winding single lane as one nears the Sign. If the Hollywood Sign became a nighttime beacon, traffic in the Canyon would quickly reach gridlock.

That’s precisely what happened on New Year’s Eve of 1999, when the Hollywood Sign was rigged for a Millennial light and fireworks show. People came up Beachwood Drive by the thousands, effectively trapping everyone in the Canyon and preventing emergency vehicles from entering. It had a lasting effect on residents, some of whom still shudder at the memory.

In the Sign’s original incarnation as a billboard, it was lit, the better to impress prospective property owners. It flashed in segments, first Holly, then wood, then land, before lighting up completely. A searchlight below it lit up for emphasis, like an exclamation point. Hollywoodland! It must have been wonderful–and to Albert Kothe, the man whose job it was to change the lightbulbs, a grim reminder of his day job. More on Kothe, a true Hollywoodland character, in a future post.

You must be logged in to post a comment.