Mary Astor at Moorcrest: the 1925 Publicity Photos

August 25, 2009 § Leave a comment

From Mary Astor’s second memoir, A Life on Film (Delacourt Press, 1967), come two previously unseen (at least by me) photos of her at Moorcrest.

In the first, she poses with her dreadful mother, Helen Langhanke. Helen, who made no secret of hating her daughter during her lifetime, underscored the sentiment by leaving Astor her diaries, which were a litany of viciousness and abuse. (Helen Langhanke’s diaries not only compounded Astor’s pain but, oddly, instilled the diary-keeping habit that would trigger the 1936 custody suit brought by her second husband, Franklyn Thorpe.)

Astor hated Moorcrest’s decor, which she called “unfortunate.” The red lotus keyhole windows and central arched window are clearly seen in the background of the photo, which appears to be the north side of the house. Here’s how the north facade of the master bedroom looks today:

Looking North to the Hollywood Sign from Moorcrest/Hope Anderson Productions

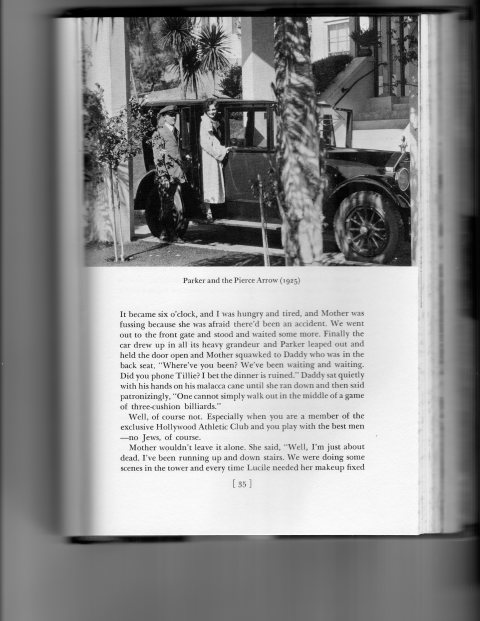

Far more glamorous and fun is the second photo. Astor poses in Moorcrest’s porte cochere with the family chauffeur and their Pierce Arrow limousine, both afforded by her earnings.

She was 19 years old, the family’s sole supporter and a virtual prisoner of her parents and Moorcrest. And though Mary Astor would attain freedom in three years, she wouldn’t reach the height of her stardom for another fourteen.

For more about Mary Astor, purchase the documentary “Under the Hollywood Sign”at http://hopeandersonproductions.com/?page_id=3361

The film is also available for rent at https://vimeo.com/ondemand/uths

The Trials of Mary Astor

July 23, 2009 § 2 Comments

Mary Astor/Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

Mary Astor is probably best remembered today for her roles in films like “Midnight,” “The Palm Beach Story” and “The Maltese Falcon,” but in her lifetime she was as famous for two notorious legal actions. In both cases, she suffered public embarassment but ultimately triumphed.

The first was a suit brought by her own parents for financial support, which Astor had recently ended. That Helen and Otto Langhanke should have felt entitled to any of their 29-year-old daughter’s earnings was illustrative of her role as a cash cow: she had been the family’s sole wage earner since her mid-teens. Otto Langhanke, a failure in all his jobs, had set his sights on a Hollywood career for his young daughter–then called Lucile–and seen his investment pay handsomely. At 19 Astor was earning so much money that her father was able to buy Moorcrest, an estate located at Temple Hill Drive and Helios Street in Beachwood Canyon. Her money not only paid for the enormous house but a staff–maid, gardener, chauffeur–and a Pierce-Arrow limousine.

As a teenaged Silent Era star/Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

Yet Astor herself had no control over her money–and except for a $5 a week “allowance” granted when she was 19, no money of her own. Otto, who was both physically and emotionally abusive, allowed her out of the house only to go to the studio–and even there she was accompanied and watched by her mother. Astor’s first love affair–or as much of one as she could manage under the circumstances–was with the charming 40-year-old John Barrymore, who eventually left because of the terms of her house arrest. (He married Astor’s fellow WAMPAS Baby Star Dolores Costello, whose mother kept her on a longer leash.)

Finally in 1926, when Astor was 20, she daringly escaped Moorcrest by climbing down a tree off her balcony and hoofing it to a hotel in Hollywood.

Moorcrest Bedroom--probably Astor's/Hope Anderson Productions

Her return was brokered by Moorcrest’s architect, Marie Russak Hotchener (see below), who had befriended the Langhankes and recently negotiated Astor’s allowance and right to work unchaperoned. “Helios” Hotchener (after whom the street outside Moorcrest is named) persuaded Otto Langhanke to let Astor go out in public on her own and have a personal checking account with a $500 balance–at a time when she was earning $2,500 a week.

Mary Astor left Moorcrest for good for good by marrying Kenneth Hawks, the director-producer brother of Howard, in 1928. Hawks, whose total lack of sexual interest in his bride was accompanied by kindness and financial generosity, insisted that Astor spend only his money for both household and personal expenses. That meant every penny of her whopping salary–up to $3,750 a week–went to her high-living parents.

The gravy train stopped running when Hawks was killed during an aerial shoot in 1930. The following year, Astor married her doctor, Franklyn Thorpe, and the couple lived frugally while her parents lived grandly in Moorcrest. It was only after giving birth to her daughter Marylyn in 1932 that Astor signed over her share of Moorcrest–Otto had made her sign a document giving her 1/3 ownership of her own house–and cut off the flow of money. Unwilling to downsize, Otto Langhanke sued. The judge dismissed the suit after Astor offered to pay her parents a $100 monthly stipend. In her 1959 memoir, My Story, she wrote: “The reporters had rather a cruel laugh at Daddy’s expense; they got him to pose on the little bridge over the pool, gazing sadly into the water, and they ran the picture with the caption: “Down to their last swimming pool.” In end, Otto put Moorcrest up for auction after refusing an $80,000 offer–and got $25,000 for it.

Astor and Thorpe divorced in 1935. Though the divorce was uncontested, Thorpe sued for custody of Marylyn the following year. Complicating matters was Astor’s diary, which included references to her extramarital affair with the playwright George S. Kaufman. After forged pages of the diary were leaked to the press, the trial became a sensation. According to Astor, “it became a standard joke at parties for some man to come in looking furtive…and say, “I’m leaving town–I’m in the diary.” Despite pressure from a consortium of studio executives to settle the case, Astor persisted and won primary custody of Marylyn. Though she expected to lose her acting career over it, her popularity among audiences actually increased after the trial. Astor entered her best professional years in 1939 with “The Maltese Falcon” and a radio show, “Hollywood Showcase,” a kind of “American Idol” for undiscovered actors.

In later decades, Astor suffered a cascade of personal trials–loser husbands, loser boyfriends, a devastating non-sexual love affair (she seems to have had absolutely no gaydar), alcoholism, financial ruin and an Everest-sized avalanch of health problems. Each time she bounced back, going back to work and learning new techniques that allowed her to transition from movies to the stage, radio and, finally, television. After finally getting sober in the 1950s, she turned to writing, publishing two best-selling memoirs and five novels.

Overcoming her horrible upbringing, Astor had good relationships with her daughter, son and grandchildren. She retired from acting in 1964 after 123 films; her last was “Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte.” In 1971, she chose to live out her life at the Motion Picture Home in Woodland Hills rather than burdening her children with her care. She died there of heart failure in 1987, at 81.

—————–

For more about Mary Astor, purchase the documentary “Under the Hollywood Sign”at http://hopeandersonproductions.com/?page_id=3361

The film is also available for rent at https://vimeo.com/ondemand/uths

You must be logged in to post a comment.