Remembering Shinobu Hashimoto, Japan’s Greatest Screenwriter–and the 20th Century’s

July 24, 2018 § Leave a comment

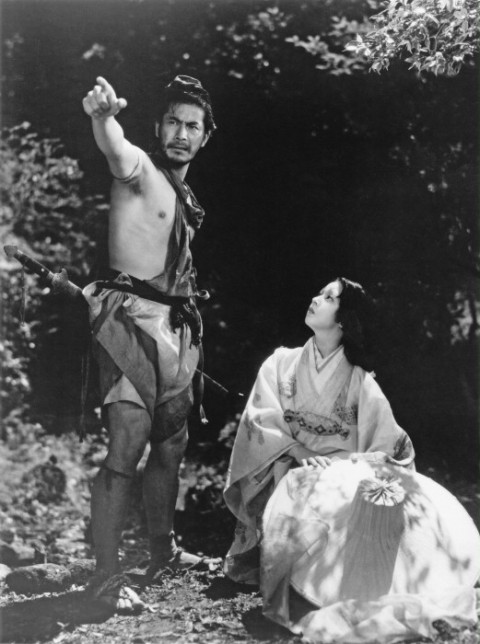

Few centenarians’ deaths come as a shock, but last Thursday’s announcement of Shinobu Hashimoto’s passing at 100 marked the end of an era. Hashimoto, whose blazing career with Akira Kurosawa began with “Rashomon” and continued through the decades with such classics as “Ikiru,” “Seven Samurai,” “Throne of Blood,” “The Bad Sleep Well,” and “Dodes’Ka-Den,” was a giant of cinema, and not just in Japan. His screenplays, whether written alone or in collaboration, have resonated throughout the world since 1950, their relevance unfaded by time and trends.

Though deservedly famous for the samurai films that brought fame to Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune, his most important leading man, Hashimoto was equally renown for his contemporary films. Poverty, wartime devastation and existential dread were his themes, and he explored them with compassion and an unsparing eye for everyday cruelty. In “Ikiru,” my favorite film of all time (if I had to choose just one), Watanabe, the dying bureaucrat, not only finds life’s meaning in his remaining two months but does so in secret because his doctor has withheld his fatal diagnosis, as was the Japanese custom until recently. Watanabe’s only son treats him with disdain and his daughter-in-law regards him as a nuisance; neither will listen as he tries to break the news of his impending death. So Hashimoto, after granting the abstemious Watanabe a brief period of hedonism, sets him on a path to greatness: creating a park from an urban swampland, against almost insurmountable odds.

In “I Live in Fear,” Nakajima, a foundry owner, is so convinced of a coming nuclear war that he decides to move his family to the safe haven of Brazil. His family responds by having him declared incompetent. “Dodes’kad-den,” explores the daily lives of impoverished shantytown residents, including a boy who lives in a fantasy world in which he imagines himself a tram conductor.

Beyond his work with Kurosawa, Hashimoto wrote for other major directors of his time. His screenplays for “Summer Clouds” and “Whistle in My Heart” became two of Mikio Naruse’s best late-period films. “Harakiri,” for Masaki Kobayashi, is considered a masterpiece.

Still, it’s not necessary to have seen any of these films to know Hashimoto’s work well. “Seven Samurai” became “The Magnificent Seven;” “Ikiru” spawned “Breaking Bad;” “Hidden Fortress” inspired “Star Wars.” And even the least cinematically inclined are familiar with “Rashomon,” which has entered the English language as a word for conflicting yet true accounts. It’s hard to imagine life without these touchstones, all of which sprang from the pen of Shinobu Hashimoto, who survived World War II and tuberculosis to forge an unparalleled and unforgettable body of work.

My related articles:

The Japanese Masterpiece at the Heart of “Breaking Bad”: Akira Kurosawa’s “Ikiru”

Awakened By Impending Death: The Transformational Heroes of “Ikiru” and “Breaking Bad”

“Isle of Dogs,” and “Mozart in the Jungle”: White Men Try to Explain Japan To Us

April 5, 2018 § 1 Comment

I have mixed feelings about “Isle of Dogs,” just as I do about other Wes Anderson films. On the one hand, it’s an homage to Japanese culture, particularly the films of Hayao Miyazaki and Akira Kurosawa. On the other, it’s a stereotype-laden tale that trots out (pun intended) every conceivable Japanese cliché: Cherry blossoms! Swords! Sushi! Megacities! Machine Politics! None of that offended me. What did were the references to World War II, particularly the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki;the post-apocalyptic Trash Island; the kamikaze-like plane of Atari, the “Little Aviator;” and the island’s deformed and wounded native dogs, survivors of laboratory experiments. For those who might have missed those references, Anderson helpfully provides an explosion with a mushroom cloud.

Anderson and his co-writer Roman Coppola apparently love Japan and have spent time there. But like countless other infatuated gaijin, they can’t resist the urge to explain Japanese culture, despite their shaky and superficial understanding of it. It’s a long tradition among white males that began with Lafcadio Hearn, an Irish-Cypriot journalist and wanderer. As the first westerner to write extensively on Japanese literature and culture, the non-fluent Hearn got so famous that he attained a professorship–in English literature, a subject he was also unqualified in–at Tokyo University in 1896.

These days, the explaining goes on less in books than in movies and television, but with the same mixed results. Roman Coppola does better in the current season of “Mozart in the Jungle,” which has several episodes set in Japan. There the orchestra performs on temple grounds and at a Tadao Ando-designed complex, among other picturesque locations. In other scenes, the Japanese love of classical music is depicted at a bar where patrons go to listen to recordings on high-end equipment. All of this culminates in a tea ceremony attended by the two leads (Gael Garcia Bernal and Lola Kirke) and conducted by a Japanese woman who is a master of the form. So far, so good, but then the characters drink the tea and find themselves in a Kurosawa-inspired bamboo forest, where they speak forbidden truths and achieve the enlightenment that they either were or were not seeking–I forget which because I’d already tuned out.

As in “Isle of Dogs,” the western fantasy of Japan collapses under its own weight in “Mozart in the Jungle,” and soon the musicians are back in New York where they belong. Japan clearly deserves better. It’s absurd that non-Japanese-speaking outsiders feel compelled to explain its complex culture to the world, but as long as there are white male Japanophiles, there will be attempts.

The Japanese Masterpiece at the Heart of “Breaking Bad”: Akira Kurosawa’s “Ikiru”

January 26, 2014 § 3 Comments

From mid-October to mid-December of last year, I did little else in the evenings but watch “Breaking Bad”–all sixty-two episodes in two electrifying months. During that time, I stopped reading books and rarely went out, the better to devote myself to the sprawling splendor of Vince Gilligan’s epic. To say that it was a compelling experience doesn’t do it justice: “Breaking Bad” dominated my thoughts, conversations and dreams. I loved it, although every so often I’d have to take a night or two off in order to get some sleep.

I wasn’t far into the first episode when I experienced the shock of recognition for an earlier work that I know very well. “Ikiru,” (“To Live”) is a 1952 Kurosawa classic about a colorless bureaucrat’s effort to redeem his life in the face of a brick wall diagnosis of stomach cancer. The film’s echoes are everywhere in “Breaking Bad,” not only in the two protagonists’ existential struggles, but in their relationships with disapproving, uncomprehending families and their formation of new and unlikely alliances with strangers. Kanji Watanabe and Walter White even signal their inner transformations in the same outward manner: by purchasing and wearing surprising new hats.

Despite the film and TV program’s very different cultures and time periods (post-Occupation Tokyo versus contemporary Albuquerque), the similarities between them are too close and numerous to be coincidental. So I wasn’t surprised to learn that Vince Gilligan, the creator of “Breaking Bad,” confirmed the “Ikiru” connection in an interview: http://www.npr.org/2011/09/19/140111200/breaking-bad-vince-gilligan-on-meth-and-morals?utm_medium=Email&utm_source=share&utm_campaign=

My exploration of “Ikiru,” “Breaking Bad,” and their protagonists can be found in Pages:

Awakened By Impending Death: The Transformational Heroes of “Ikiru” and “Breaking Bad”

Setsuko Hara at 90: Ozu’s Muse, Forever Young

August 18, 2010 § Leave a comment

Setusuko Hara is an actress with no equivalent in western film. For 20 years after WWII, she defined contemporary femininity for Japanese audiences, first playing young, unmarried women, then wives, then mothers. In all her roles, she was a vital, central character, never an adjunct to a male star. (If only the same were true for female characters in American films!) So totemic is Hara’s place in Japanese cinema that she earned the moniker “The Eternal Virgin.” By refusing to grow old onscreen–she made her last movie at 46–and never marrying in real life, she further set herself apart, not only from other actors but societal norms.

Although Hara made 73 films in her 30-year career, she is best known for the twelve she made with three major post-war auteurs: Akira Kurosawa, Mikio Naruse and Yasujiro Ozu. A more detailed essay on her life and work can be found in my Pages.

You must be logged in to post a comment.