Art and Posterity in New York: Part I

August 11, 2014 § 1 Comment

I’ve been spending a lot of time in New York lately, which has been a welcome change from my usual summers in Los Angeles. My last trip in June was very theater-centric: four plays in seven days. This time, my visit was devoted to visual art: two days at MOMA, one at the Whitney and one at Dia Beacon, in the Hudson River Valley.

My first stop was the Whitney’s huge Jeff Koons retrospective, a mid-career exhibition that took up four floors and the sculpture garden. I went in hopes of overcoming my love-hate reaction to Koons’ work, but emerged hours later feeling lukewarm to cold about all of it. Nevertheless, seeing the sculptures and paintings at close range increased my admiration for their meticulous craftmanship: it’s obvious that a great deal of skilled labor went into each one. My negative reaction was aimed at the conceptual level–significant because concept is all that Koons does at this point. Regardless of medium, all his works are created not by him but by a team of artists, who (along with support staff) currently number 140.

For years I’ve delighted in the balloon dogs and suspended basketballs of Koons’ early career, as well as the giant topiaries (“Puppy,” “Split-Rocker”) of the past twelve years. But at the Whitney, in rooms of lighted vitrines full of vacuum cleaners, sculpted blow-up toys, giant Play-Doh sculpture and large format photo paintings, the charm of Koons’ work faded. “Play-Doh,” a monumental and life-sized colored rendering that took a decade to make because of technological difficulties, was a particularly vivid example. Standing before it, my only thought was why? Similarly, his porcelain sculptures–such as “Michael Jackson and Bubbles”–were both technical marvels and conceptual blanks. Looking at them, I could glean no greater meaning than what appeared on their shiny surfaces.

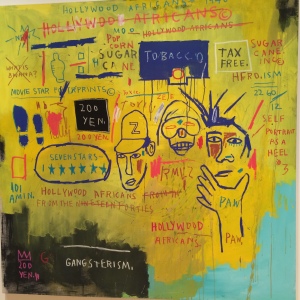

The permanent collection acted as a palate cleanser for the Koons exhibit. I found solace in a room full of Agnes Martins (“The Islands”) and a wall of Ed Ruschas. Even the Warhol Brillo boxes seemed masterful in comparison to the Koons Play-Doh and pool toys. And Jean Michel Basquiat’s painting “Hollywood Africans”–regarded as a daring example of street art when it was new–seemed rigorously formal thirty years later, or perhaps just in contrast to the Koons retrospective.

I had a better experience with “Split-Rocker,” (top) Koons’ topiary in Rockefeller Center. Even more than “Puppy,” “Split-Rocker” is a multi-faceted delight: not only because of its dual pony/dinosaur face but because it looks radically different at different distances. It’s a grey-green monolith from a great distance, a huge flowering toy from middle distance, and a fascinating collection of flowering plants close up. There’s even a ribbon of mirror that reflects viewers.

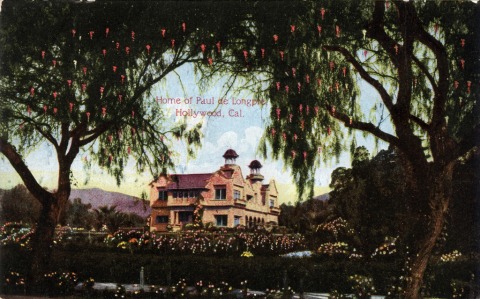

It’s a given that Koons is the most commercially successful fine artist of his generation. The question is whether his work will be well-regarded, or even remembered, beyond his lifetime. Will he be another Marcel Duchamp or another Paul De Longpre, whose paintings were all the rage during his lifetime and instantly forgotten after his death? Questions of art, commercial success and posterity were very much on my mind when I had an illuminating encounter a couple of days later. More about it in Part II.

Hollywood Before the Movies, Part III: Mansions and Streetcars

July 6, 2010 § 5 Comments

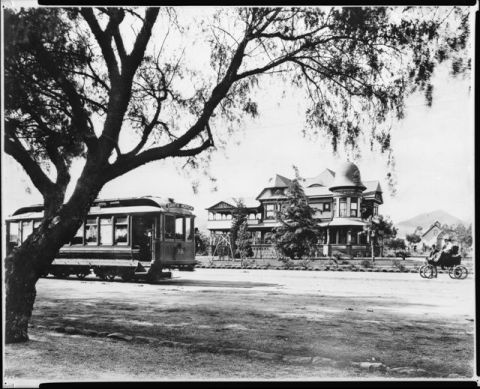

The E. C. Hurd Residence (Hollywood Blvd. & Wilcox) in 1900/Courtesy University of Southern California Archives

The turn of the 20th century was also a turning point for Hollywood. No longer a farming community of like-minded Christians but not yet the seat of the movie industry, the village of Hollywood briefly became a garden suburb for the newly wealthy.

Among this second wave of Hollywood settlers was E. C. Hurd, whose sprawling Victorian home is pictured above. Hurd dug his fortune from the mines of Colorado and invested it in a prime Hollywood tract, on which he built a mansion and planted a lemon grove. Here we see his estate on the north side of Hollywood Blvd., with an early motor car–presumably his–to the right. Only the pepper tree in the foreground hints at agriculture; far more portentous is the Santa Monica-bound streetcar on the left. Part of the Pacific Electric Railway Company’s growing inter-urban network–soon to be the world’s largest public transportation system–the trolley car took passengers from downtown Los Angeles to the beach, though Hollywood probably was the more popular destination.

Beyond the obvious, the photograph foreshadows Hurd’s own future in business. He would soon purchase the Cahuenga Valley Railroad and extend the line to Laurel Canyon, opening it to residential development.

Perhaps the most famous Hollywood transplant of the time was Paul de Longpre, a French horticultural painter who arrived in Los Angeles with his family in 1889. After de Longpre discovered his ideal flowers growing in Hollywood, he met Daeida Wilcox, who was so anxious to attract culture that she gave him her homesite, three lots on Cahuenga just north of Prospect (later Hollywood Blvd.), for his estate.

The mansion and gardens Paul de Longpre built not only drew Hollywood society but served as a lure for new property buyers and tourists. So many visitors came to see “Le Roi des Fleurs” that the P.E. Railway added a trolley spur on Ivar Avenue to deposit them closer to the estate. Tours of the house and gardens, along with prints of his floral paintings, supported the de Longpre family until the artist’s death in 1911. After his family returned to France, the house and gardens were demolished for their valuable real estate, and de Longpre’s paintings–romantic still-lifes of roses, orchids and the like–fell permanently out of fashion. If not for De Longpre Avenue, most Hollywooders today would not recognize his name, let alone his art.

Coincidentally, 1911 was the year Los Angeles’s public transport system became the world’s largest, with 1,000 miles of track. In Hollywood, the year not only marked the end of de Longpre’s era but the beginning of another, as a new wave of residents discovered the town: movie people. More on them in future posts.

Additional Sources:

Kevin Starr, Inventing the Dream: Southern California Through the Progressive Era. Oxford University Press, 1985.

Gregory Paul Williams, The Story of Hollywood. BL Press, 2005.

You must be logged in to post a comment.